Anodyne Opinions

Scene: you wake up out of a day-dream and find yourself in the middle of a business meeting. Everyone is staring, waiting for you to say something. What do you do?

Say any of these things below and 9 times out of 10 it will not seem like a non sequitur, and nearly everyone will think you are Very Smart™:

- We need to define success metrics.

- We need more ambitious goals.

- We need to go faster.

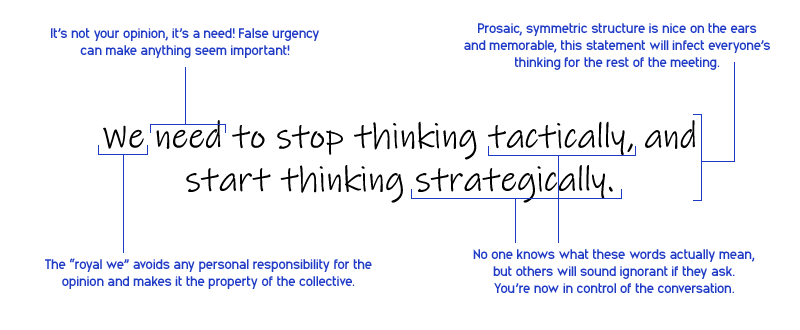

- We need to stop thinking tactically, and start thinking strategically.

- We need to think long-term--what does this look like N years from now?

- We need more headcount/resources before we can do that.

- We need more data to make a decision.

- We don't need more data, let's make a decision.

- We don't need policy or process; we need a culture change!

- We need fewer meetings.

- We need to sync more often.

- We need to do a postmortem/retrospective.

- We need more documentation.

- We need someone to own this.

- We need a working group/task force/tiger team.

- We need to standardize/deduplicate.

- We need to talk to the customer.

- We need to break this down so it fits into a sprint.

- We need to [cut some corner], but we'll fix it right after.

- We need a plan/proposal/design doc.

- We need a single source of truth.

Anodyne opinions unraveled

I call positions like these anodyne opinions because they verge on being truisms, if not popularly held misconceptions, while also employing a clever rhetorical structure that makes them downright insidious:

Problem #1: anodyne opinions are infinitely defensible

These sorts of "non-positions" cannot be productively discussed in a group setting as their opposite sounds almost farcical: "no we shouldn't talk to the customer." People innately rely on these short hand emotional judgments during spur-of-the-moment debates because deeper thought takes time. As a result, any opposition will be working at a disadvantage from the very beginning.

How do you argue against "more data" or "being in sync?" If you try, the discussion usually turns mind-bendingly meta: "culture change would be great, but that is difficult to achieve without small incremental steps to get the ball rolling." Now you're no longer discussing the issue at hand, but business/management theory and organizational dynamics...domains that are mistreated by laymen and thrive off personal preferences masquerading as wisdom.

The only way to defeat bad opinions, it seems, is more bad opinions.

Problem #2: anodyne opinions thrive off power dynamics

Who says something is almost as important as why they are saying it. These perfectly fortified opinions take on a life of their own when power differentials enter the equations because the personal cost of speaking out far outweighs the benefits of nodding along. What's a few days writing a useless design doc when you can make your boss feel good and like you more?

We are often unware of (or unwilling to acknowledge) power differentials so you may be running afoul of this without realizing it. Power can come from many places:

- Explicit: managers (at all levels) are responsible for people's livelihoods which is the closest thing to "life or death" on this list.

- Role-based: technical leads and mentors hold less authority than managers but are granted a lot of deference.

- Expertise: holding an outsized share of knowledge, or having a particular job level (senior/staff/principal), implicitly puts pressure on everyone around you.

- Relational: "early hires" hold a lot of sway regardless of official role because of the proximity to leadership stemming from being employee #15 or whatever.

- Structural: members of the majority have privileges that their underrepresented peers do not: chiefly the ability to speak out with impunity.

...and many more. Power literacy is just as important for those with power as it is for those seeking it.

Problem #3: anodyne opinions waste time

If these opinions effectively have no content, what's the harm? Wasted time, frustration, disillusionment. Each such position motivates a lot of extra work. The extra overhead makes everyone feel unproductive. It puts the brakes on new (but fragile) ideas because they often cannot stand up to the scrutiny of a cost/benefit analysis or a detailed project plan early on. Your team will start feeling like this isn't a place where they can be productive or innovative.

"We need more data." Someone has to collect, clean, and analyze it...not to mention all of the subsequent discussions. "We need to define success metric." It takes time to identify measures worth committing in such an official fashion, and that doesn't even account for the added overhead of everyone involved continuously bending their work in service of these success metrics.

None of these things are innately bad mind you...but if they were entirely motivated by no more than a powerful person trying to sound smart in a meeting, then it's all in service to nothing.

Contributing constructively

Before you fly into rage, know that I have sincerely said all of these things before...and still do on a regular basis. The issue is not the sentiments themselves, but rather why and how they are being said at all. Hence it is better to think of these opinions not as innately "anodyne" but rather "dangerous." Dangerous in the sense that if wielded irresponsibly it will do harm to you, your projects, and your team.

Check your motivation

Speaking up for the sake of speaking up (appearing smart, scoring points, etc) is not a sound reason to share an anodyne opinion. Good leaders know when their input is critical and when it is superfluous. If asked directly for your opinion when you have none, be honest: "I have nothing to add at this time, it sounds like you're on the right track, I'll let you know if I think of anything else offline."

Speak candidly

I see a lot of anodyne opinions come out because someone disagrees, but is not willing/able to be honest.

Consider this scenario: someone is discussing their chosen approach to a project in a team meeting. You disagree with some of the technical decisions, but don't want to so "publicly" call out the individual and put them on the spot; you're not even sure you're right and don't want to seem like a micromanager. Instead you reach for an anodyne opinion that will steer them towards rethinking these decisions: "some of this seems pretty complicated, we really need to get an MVP out the door and iterate based on customer feedback."

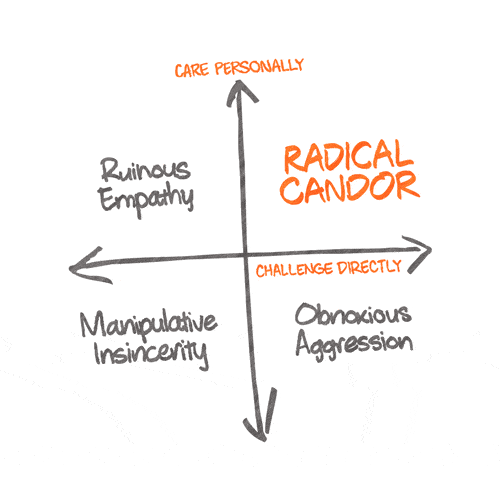

You've fallen into what Kim Scott calls either "Ruinous Empathy" or "Manipulative Insincerity." Failing to speak honestly and challenge directly can lead to a lot of wasted time and frustration as both sides keep "taking past each other." Overcorrecting the other direction (into "obnoxious aggression") will surely avoid anodyne opinions, but come at a much greater cost in the long run.

If, after considering what's right for both the people and project before you, it still seems like one of these positions is the right choice, then you can proceed.

Include context

Once you've resolved that one of these dangerous opinions is the necessary and right position to espouse, pay attention to your delivery.

Don't just say "we need more data." Explain why you believe that to be true, including any assumptions you are making (either about the problem or the beliefs of others in the room). While it is almost impossible to argue against "more data," it is much more plausible to refute the reasoning behind your statement and thus have a productive discussion.

Putting it all together: delivering a constructive opinion

Here is an example combining all of the above advice:

Earl, you mentioned that it will take a couple months to get this product rolled out to the early adopters. Since a lot of the benefits of Project X require customers to also change their habits, I assume that it will take a long time (1+ year) before we know if this idea is going to work. Therefore, I recommend we come up with some success metrics that can be used to gauge our progress and course correct as needed, else I worry we will spend a lot of time for not very much gain. Do you think that will help or just be a tax?

- All assumptions are stated up front so no one is second guessing why you might suggest this.

- Your understanding of the concept at hand is restated in your own words, inviting corrections.

- Ending on a leading question suggests that you're open to hearing contrary opinions.

I can confidently state that no one I work with is an "empty suit." Nevertheless, I've been in plenty of discussions that devolved into a circular exchange of anodyne opinions. This is a natural side effect of working in a professional environment, and thus a phenomenon that needs to be explicitly kept in check....lest we all lose the ability to communicate except through increasingly inscrutable managerese.