27 Lessons from 8 Years of Management

Today I'm switching back to being an individual contributor.

It's perplexing that this is something that evokes a mix of shame / exhilaration / terror / hopefulness / dejection. Like telling your Mom, "I'm the one who broke the vase, not the dog" and feeling relief that the lie is over but then waiting for the punishment (speaking of, I haven't even told my parents yet, there's gotta be some childhood repression going on there). We can pretend that status doesn't matter, that the manager/IC dual track system means there's no loss here, but try telling your hierarchical monkey brain that.

I'm no stranger to the engineer/manager pendulum. While the term was first coined (popularized?) by Charity Majors in 2017, I've been "pendulum-ing" long before then (17ish years)...this will be the 6th swing of pendulum. In spite of the familiarity of the maneuver, this time feels different. 8 years is a long time–this is my longest contiguous stay in management. On one hand it is exciting to go back to hands-on building things amidst a paradigm-shifting moment in tech. On the other hand, it's hard to escape dread at the thought I might be throwing away years of "career progress" on a whim.

Now feels like the perfect time to chronicle some hard-won lessons from my most recent turn at the wheel; I've grown more as an engineering leader in the last few years than at any other point in my career.

My Recent Roles

First some background on what I've been working on so you can place these lessons in context. Over the last 8 years, I have...

- Served as the head of engineering for a B2B OT security startup eventually acquired by Rockwell Automation, building their product development team from scratch.

- Joined Google and managed the foundational storage systems that hold all of Google's data, (blob, object, file, and configuration storage) in addition to distributed system primitives used by all products and services at Google (locking, leader election, time, key management).

- Switched out of platform engineering and back into product engineering becoming one of the overall engineering leads for Google Drive.

During that time I've had to rebuild and re-establish myself in a new org–scaling from running a single team of 3 engineers to an org of 70+ not once but thrice! I've acted as the "pure people manager" and tech lead manager (TLM) role for which Google is notorious (infamous?). At times I've had 25 direct reports (oh my god), other times a proper pyramid of managers and sub-teams. I've received multiple promotions, and helped others grow from L3 all the way to L8. If you believe that "10,000 hour-rule" for mastery, I'm well past the 10,000 hour mark when it comes to management. I run a thriving management coaching business on the side.

None of this is to brag, but rather to establish...

- This isn't the ranting of someone who burned out and couldn't cut it.

- Most of my lessons are applicable to navigating and thriving at BigCo–the FAANGs of the world–you may find some portability of these lessons to other contexts but that is only incidental.

Without further ado, let's dive in.

Org Dynamics

1. Small business experience does not prepare you to lead in a large enterprise.

It's a story as old as time: director+ startup leader joins BigCo and gets "downleveled" to small team manager. I've heard this explained away as elitism or just differences of scale (a startup director might have 20-30 reports...while the enterprise equivalent is 60-120). I've run across plenty of these people at Big G and they all have a chip on their shoulder, seeing this fate is wholly undeserved. I was one of them...at least until I realized how much I had to learn.

- Change management and project execution when you have to deal with tens-to-hundreds of stakeholders with different reporting chains and incentives is a much greater challenge than doing the very same with a small group that reports to you / was entirely hired by you / has to listen to you. It's the difference between learning the rules of a game versus inventing the game in the first place.

- Delivering impact now requires navigating an entire layer of organizational optics and processes which likely didn't exist where you came from. Building alliances, managing perceptions, and creating opportunities for serendipity (luck) will contribute more to your success than pure brute force execution.

- There's specialized functions for everything (product, UX, design, marketing, support, SRE, etc) and you have to learn how to get what you need out of them without any formal authority and without seeming like a dictator.

- You will work on timescales that seem unthinkable in a startup. A major initiative in BigCo might span 3-4 years. Your entire company could be born, live, and die in less than half that timespan. Maintaining the endurance to be consistent over such large time scales will push you to your limit.

- Hiring, engaging, and motivating the typical BigCo employee is an uphill battle. You have less agency and autonomy to pick what you work on, you often need to sell very bright engineers on lame projects (aka cat turds), and you have fewer incentive levers under your control (titles, money, promotions). There's little chance for "mission" to motivate and the median BigCo worker is more driven by status and wealth (tech has become a "prestige" field like law and medicine, you will be surrounded by people who are not here for a love of engineering).

This is not to say that startup/small biz experience isn't helpful. You wear more hats and often build a more complete, ecological view of the value stream that is software engineering...understanding how "code" gets turned into "profits." You'll build product intuition, commercial sense, resourcefulness, self-reliance, and the ability to work with all manner of stakeholders that will set you apart from a life-long BigCo manager....but don't delude yourself into thinking this means you'll totally crush it as a director on day zero. Downleveling is a myth.

2. Org structures are a fun bike shed but reality will eat your perfect org chart for breakfast.

You've read Team Topologies (and An Elegant Puzzle, and Scaling People, and Thinking in Systems, and....). You quote Martin Fowler and opine about the "Reverse Conway Maneuver" daily. You have sat in poorly structured orgs and wondered why the directors and VP's in charge are totally asleep at the wheel with teams that overlap / lack a clear mission. You think "when I'm in charge, we'll get the org shaped up and everything else will follow!"

Ha ha, hahahaha, ha.

No no, I'm not laughing at you, I promise. I used to think like this, waiting for my chance to join the big leagues and run my own org where I'd show the power of proper org design.

Now that I've run four major (100+ people) reorgs in my life I've come to understand a really painful truth: 80% of the time, the shape of the org chart just does not matter as much as you think.

In my experience, a highly optimized org chart only stays optimal for about 3 months before something breaks:

- A major shift in strategy, priorities, or objectives means you have a massively oversized (or undersized, or nonexistent) team for a given area/project/piece of infrastructure.

- A staffing crunch forces you to raid one of your "perfectly crafted" teams and have someone pinch hit for another group. This keeps happening until your "org chart" is a spaghetti mess of dotted lines.

- A TL or manager whom you built the org around quits on you, throwing the whole system into chaos.

- A key playmaker gets antsy for more opportunities to grow and demands more scope / more reports and you can't imagine losing them.

We used to get out of these messes by just...hiring more! Why change a team when you can grow an entirely new one!? Well those days are done–the money printer is broken–and you definitely cannot run a reorg every 3 months. Engineers benefit from stability in their working relationships. Once a team is bonded and works well together, your best bet is to "bring a problem to the team" rather than "bringing a team to the problem" even if it means subtly pivoting what a given group owns.

Naming teams sure is a bitch when you do this (I literally had a team that called themselves "the variety show," hi Matt), but having a vague/inaccurate name is better than going through the Tuckman cycle constantly.

With this in mind, what really matters for organizational clarity and success is...

- Clear lanes of accountability: every major area has a directly responsible individual (DRI) or single-threaded leader (STL) and those individuals are held accountable for results. With ultimate accountability comes ultimate authority to do what needs to be done no matter whose reports / teams are involved.

- A conscientious and high-agency leadership bench: these individuals take action without waiting to be told and never assume it is "someone else's job." Such leads are self-driven and don't let gaps in team structure and org process hold them back.

- A sense of ownership: your team hinges a non-trivial amount of their self-worth on rising to the challenge. When teams feel like their work is their own, you receive an outpouring of effort, energy, and creativity that leads to better outcomes than any amount of micromanagement.

- Strong interpersonal relationships and conflict resolution habits: the team is able to engage in creative conflict, disagree productively, and puts in active effort to improve their relationships. Things get messy when your org chart is messy, people have to fundamentally care about and respect one another if this is going to work.

Don't get me wrong–there is great power in enabling productive non-communication so that each part of a large org can function independently and avoid conflicts. There are benefits to aligning management (and corresponding performance management practices) to the work actually happening. You can't go to full blown self-forming teams and holocracy without leaving a lot of productivity on the table.

The point is that your team structures will always carry some non-trivial amount of "org-debt" and "misalignment" in exchange for stability of teams, retention of key talent, and enabling the flexibility to respond to emergent threats/crises/opportunities which are much more important to long-term success.

Another way to think about this is that if you wait long enough, some emergency will emerge that forces a reorg (e.g. a top manager wanting to go back to being an IC...lolsob) so there is little need for you to proactively initiate such destructive changes. You'll likely prematurely optimize around a set of constraints, people, and goals that won't hold in just a few months!

3. Cross-functional incentive misalignment is your number one enemy.

Different job functions–e.g. product, eng, UX, data science, etc–optimize for different things (duh). Unfortunately you have to work with all of these functions to get anything done in BigCo so you cannot simply plug your ears and insist eng is always right.

The most pernicious form of this I have seen occurs at Google: functional silos. Functional silos are entire reporting chains (managers reporting to directors reporting to VPs reporting to...yet more VPs lmao) of the same job function. An eng manager and a PM manager that co-own the same objectives don't actually share a common ancestor until you reach the SVP or the CEO.

You might think "that's fine, I can just...talk to the person...so who cares?" but the reality is that all of your closest collaborators work for different bosses. As much as we try to be our own person, success at BigCo largely means figuring out what your boss really wants. You are directly incentivized in the form of career growth/$$$$/power to prioritize what they think over the collective opinion of your peer group. See where this is going?

I had the dubious honor of leading about one-third of Google Drive's product portfolio, and with that came a veritable army of co-conspirators (product managers, designers, UX researchers, data scientists, support personnel, program managers, and enterprise account managers). We would spend days...weeks!...discussing/researching/analyzing to align on a direction and a strategy. Just when I thought everyone was aligned and we were off to the races, someone would blunder into the room and say: "I spoke to [director] and they really want us to focus on [some random crap]!" Boom. Complete reset. Weeks of progress and influencing undone. Back to square one. Just because of an off-hand, drive-by remark from a distracted senior leader.

Inevitably, I would reach out to this director and find out they had no intention of randomizing us and didn't expect anyone to index so heavily on their opinion. Go figure.

To keep any group headed in the same direction, you need alignment one level up (at a minimum). What this means in practice is arming your boss with a viewpoint, facts/data/analysis to back it up, and sending them off to do battle with their peer directors/VPs/what have you. If you're precocious, you could try directly influencing these organizational Aunts and Uncles...but more often than not all I got was confused looks, "why are you talking to me? Is your Dad home?" Hurray for hierarchy! Culture eats strategy for breakfast and all that tired shit.

I'm quite fond of how Microsoft does this (used to do this?) where different functions (the "triad") would report together much lower in the org chart...sometimes as low as a "group manager" (M2) if not director (M3). There are still bugs that have to be worked out in that system but at least you have a fighting chance of keeping your group aligned.

4. You have to be just a little difficult to get things done.

If you haven't gotten the clue yet from my writing style, I can be a bit brusque. There's a method to the madness however. Not everything can be driven by consensus–do any of these scenarios sound familiar to you?

- A peer team rejects a feature request that blocks a major project.

- A dependency has a huge outage and doesn't seem to be taking it seriously.

- Your team spends all its time responding to questions and supporting users even though you have other priorities.

- Your team keeps accepting unplanned work and feature requests to help out others, delaying a major deliverable.

- You keep getting sucked into forced migration mandates because some other team "cannot" support a piece of legacy infrastructure any longer.

- Your PM presents a totally coked up PRD for a feature you think is a waste of time. You do it anyways.

- Your designer presents a mock which will double the engineering effort for a trivial UX optimization in your opinion. You do it anyways.

- Your SWEs present an over-engineered design that makes a project 10x harder than it needs to be. You do it anyways.

All of these are scenarios where consensus is the easy way out. You avoid conflict and let the bad outcome persist. You tell yourself you're "trusting the process" and empowering others to feel ownership...but what's the difference between this and outright abdication? This is why I have such a bone to pick with "servant leadership" but I'll talk about that more further down...

Sometimes you need to be the bad guy. You need to push back, be demanding, hold a higher bar, and not accept the facts as presented at face value. Another form of this is not letting others place demands on your time. There is a huge opportunity cost when a leader gets sucked into a never-ending circular debate or picking through pointless desiderata. A day spent thinking ahead and strategizing could save years of effort down the line. Sometimes you just have to make a decision and refuse to elaborate further. "No." is a complete sentence.

To some this will be read as "being an asshole." To others it's "being assertive." Honestly it's a little bit of both.

I call this "calibrated aggression." Calibrated aggression is necessary to think laterally and break through the web of lazy defaults, implicit constraints, convenient decisions, and post-hoc justifications that all too often shape our collective behavior. So much of our lives are implicitly ruled by conflict avoidance but you cannot afford to fall into this trap if you manage people.

The human mind displays a remarkable capacity for rationalization. This occurs when people create post-hoc explanations to justify their actions, even though they know (consciously or unconsciously) that these explanations aren't the real reasons behind their decisions. Rationalization is closely connected to cognitive dissonance reduction, which is the underlying psychological mechanism that drives this behavior. When there's a conflict between our actions and our beliefs or self-image, we experience cognitive dissonance–an uncomfortable psychological state. To resolve this discomfort, we often rationalize our actions by creating plausible-sounding explanations that make our behavior seem more reasonable or justified.

The key aspect of rationalization is that people often don't realize they're doing it. They genuinely believe the post-hoc explanations they've constructed. This is to say: you won't even be able to tell you've fallen into people pleasing and conflict avoidance!

Leaders being overly agreeable foment the conditions for this collective psychosis and create utterly ineffective organizations where lots of work is happening but its the wrong work and everyone feels stuck doing it. Requirements are often flexible, goal posts can be moved, and stakeholders who seem utterly cantankerous are more pliable than they seem. All it takes is a little calibrated aggression.

5. "Tech lead" is a set of responsibilities, not a title you bestow.

I think everyone has been on a team where the official tech lead (TL) seems to be doing...nothing. Crazy nuanced design decisions? They aren't the one making them. Technical debate boiling over during standup? They have nothing to say. Managers asking for the impossible and ignoring reality? They go along with it. Need something from another team? You're on your own.

You might think this is a performance issue...well, it is, BUT the real root cause 9 times out of 10 is that the manager showed up, crowned the apparently most senior person TL and just assumed they would start doing the job. You might think you would never do that, but consider what happens when your current lead leaves: you immediately rush to name a new TL because, well, you need one...right!? So you carefully choose the highest potential impact player you have and...hope they just start doing the job without prompting. Gee wiz.

The consequence of this is stark. Key leadership tasks go unaddressed. Highly motivated team members become increasingly frustrated by the lack of support or by the extent to which they are doing the TL's job without recognition. Any natural leaders will hold back (these people get activated by power vacuums–an internal locus of control coupled with a strong sense of duty encourages them to step up and grab the wheel so the ship doesn't crash–having a bench warmer in the TL seat fills the vacuum and prevents this positive instinct from bearing fruit). In short, your team will suck and everyone will know + be mad about it.

The TL role is the single most important job on the team. Even more important than the manager. You cannot afford to have a bench warmer for a TL. To avoid this unfortunate fate, you must be unshakably confident your appointee is prepared and motivated to do the (sometimes thankless) job and all the grungy work it entails. I have found the best way to be certain is to leave the TL role unoccupied and see who steps up to fill the void. These emergent leads earn the respect and followership of their teams through skill and dependability, not title. Moreover, they take action without being asked and never assume "that's not my job." That's ownership. REAL ownership. That's your TL. By the time you place the TL crown on their head, it should almost feel like a formality. And if they stop doing the tasks demanded of a TL? Then they aren't the TL any longer! You can't expect someone to stay consistent over years and years–energy waxes and wanes as life throws you curve balls–make room for TL's to step aside with grace and dignity when the time is right. This is much easier when they don't need to be divorced from an official title.

To learn more about the fundamental traits of the best TL's, check out The Captain Class by Sam Walker. Maybe one day I'll do a post on how this maps to tech.

Skip-leveling 101

6. Code is DRY, people are not.

Much ink has been spilled about the importance of vision and strategy, and communicating that to your team: helping them connect to the why of their work and empowering the team to make better decisions on the ground, all while gliding collaboration and cross-team alignment.

To get your whole org on the same page, you carefully craft the greatest all-hands of your life. Truly a magnum opus of business strategy and showmanship. You practice, practice, practice. The day arrives, your org filters into the room, and you nail the delivery. In your head you're flying high: I did it! I'm the best boss in the world. This will be the most inspired and motivated team EVER!

Fast forward, it's a week later, you walk into a skip-level 1:1. Your report complains about the project they're assigned to...they don't get why it's happening and it feels like we work on a smorgasbord of random junk that doesn't add up to anything. You refer them to the all-hands recording, and repeat some of the key messages. You patiently answer some of their questions and help them understand the message. They leave at least pretending to feel better but you're left scratching your head: "were they just not listening? Was I unclear? Did something happen I don't know about to shake their confidence in The Plan?"

Here is a cold, hard dose of truth: you are not as important as you think you are. You are not the sun and moon and stars for these people. You are just one of their eight different bosses who are all constantly saying words at them and polluting the airwaves. Worse, the supposed "priorities" feel like they shift every other month. Any sufficiently tenured BigCo employee is completely numb to this and implicitly understands that their day-to-day life is no better if they get really invested in what the boss is saying today (in fact, sometimes it gets worse if you hang your motivation and happiness on a new direction that gets shot in the head shortly thereafter).

I'm a pretty good orator, but no rousing speech has ever created the singular focus, alignment, and energy that I want for my team.

The secret? Repeat yourself. Over and over and over. The magic number is 3. Repeat the same thing in 3 ways in 3 different venues and it will start to stick. Consistency of message is key. You want to evince "this time is different, you're working for a team with clarity of purpose and direction that isn't going to just totally shift in a few weeks." Encountering the same idea at different times expressed in different ways increases the likelihood it will "click" with everyone eventually.

That all-hands is just one step, you have to keep going. There's a time and place for one-to-many unidirectional communication...but don't forget the importance of one-to-one bidirectional chats. After big town halls, I like to switch into "door-to-door salesman mode" and have a round of 1:1s. This gives me a chance to tailor the message to each person and answer their individual questions/doubts. Use memorable sound bites and consistent names for different initiatives and strategic pillars. As these ideas get repeated in different meetings/docs over many months, the team recognizes "this is all connected and part of the same thing." Yvette Pasqua has a great talk on choosing the right communication medium as you lead your team through change.

7. Light one fire at time.

You are not the fire fighter in your organization...you are the fire starter.

- Your reports (and especially your skips) will put way too much weight behind every comment you make. One sternly worded doc comment could send an engineer into a self-doubting tailspin. A random throwaway technical hot take at lunch could unintentionally pivot your team's entire technical roadmap.

- "Solving problems" at your level often translates to hiring/firing managers and TL's or canceling/starting huge new initiatives. All of these things cause massive churn and panic and none of them are clean.

Very rarely do you get the chance to build an org from scratch; you will inherit someone else's mess (sorry Matt, Yi, Cheryl, and Brian). Failing manager? Getting rid of that person is a full time job, and picking up the pieces afterwards is a full time job-and-a-half. Failing project? Good luck diving into the weeds with 2 layers of people obfuscating the details and actively trying to convince you how great a job they are doing.

If you immediately act upon the many inherited problems, you would instantly burn out. To deal with this you must limit yourself to lighting one fire at a time. Every team you "perturb" is just such a fire that will demand your active attention until it is fully resolved (unless you want to do the executive swoop-and-poop I guess). The corollary to this is being OK letting some teams suck for awhile...you have (a single) bigger fish to fry. At the rate one can realistically fix big weighty org problems, this also means you might be juggling the hot potato of a semi-dysfunctional org for multiple years. Get comfortable.

(I am trying very hard to mix as many metaphors as possible, how am I doing?)

8. Get really good at neutralizing conflicts.

Being in middle management is like defusing a bomb while wearing oven mitts.

You'll hear about problems and usually have to work through others to solve them. You channel your best, most wisest feedback to the local lead only to find out it didn't work 3 weeks later. "No, not like that," you think, "if only I was in the room, I could show them how it's done."

Getting directly involved is no better, it sends a very strong signal that "I don't trust you." Now you have two problems. Moreover, your voice carries, and the team will have a tendency to snap to your opinion...prematurely ending debates before everyone is heard and all options explored. You'll never know for sure what people really think because at least some percentage will mostly try to figure out ways to appease you...or to somehow say "you're wrong" without saying it out loud. Now your nice simple technical disagreement is a hall of mirrors filled with all the smoke people are blowing up your ass. Good luck making sound decisions, weeeeee!

This is something I have always struggled with because it's very easy to revert back to "being the TL" and directly solving the problem. Taking off the starchy, ill-fitting suit and putting on the comfy, well-worn hoody of yesteryear. All this director-ing is hard and scary and frustrating, but "being the TL" is something you've mastered!

Breaking this habit require feeling equally comfortable "managing at a distance" and steering groups towards the right outcome without them even realizing you're doing it. As with all skills, I think the best way to start out is following a framework/recipe so you can get a feel for the maneuvers involved. Once it feels natural, you can start to freestyle.

Here's my technique for refereeing conflict:

Midwife other's ideas: make your role in debates the "translator-in-chief." Listen deeply and carefully to the positions others are expressing. When you speak, it should be to clarify and strengthen others' points, or to gently correct if something has been misinterpreted. Your primary goal is to ensure no one is talking past one another, that all ideas offered are treated with respect and due consideration, and that room is made for the quietest voice. When everyone leaves, the debate might not be over, but each person ought to be able to write down exactly what everyone else believes and wants accurately. Accurate and empathetic understanding is the firm foundation from which a pool of shared meaning can be constructed, and a way forward found.

Good questions: thought provoking questions can be used to illicit deeper thinking and consideration without showing your hand. For example, here are three questions I love to use when something goes wrong and you must decide what to do next–

- What do we now know about what doesn't work?

- What assumptions led to these outcomes?

- What risks are we exposed to now that need to be mitigated?

I find literature on coaching to be a great source for these sorts of questions.

Nudge interlocutors towards mutual understanding: in one-on-one settings I will test how much active listening is actually happening by posing the question directly, "John, tell me in your own words what you think Jane is pushing for here and why she thinks that." Usually I'll get a very facile, incomplete, uncharitable account of the opposite side of the debate. When that happens, I will give my report an assignment to go out on an "idea safari"–to observe non-judgmentally and without interference the thoughts of others and to report back what they found. I do not let up until they can represent and defend their opponent's ideas as vigorously as their own. Sometimes this takes 2 or 3 one-to-ones and "safaris"...you can imagine the frustration that evokes, but it's worth it. Being able to live in someone else's head for a time is a skill that will pay off for the rest of one's life.

Write a fork doc: once good mutual understanding is established, I bring structure to the remainder of the debate through what I call "fork docs." Fork as in "fork in the road." Fork docs are very simple–usually one page–they articulate the problem statement, the must-have traits of an acceptable solution, a purely factual summary of the alternatives under consideration, and decision-making rules (i.e. whose the decider). Fork docs let you put up some constraints without having to directly express an opinion. They defuse debates by naming the core disagreement and articulating the rules by which a final outcome will be decided.

9. Ten percent turnover is the norm; someone is always dying.

As the size of your team grows, you must get a lot more comfortable with higher baseline levels of chaos and tumult.

When leading a small team of IC's, a single person quitting feels like disaster. A category 4 hurricane of dashed dreams, personal heartache, and self-doubt: "am I really any good at this people management thing?"

Once you manage 50+ people, that's a Tuesday. You should expect approximately 10% of your org to turnover every single year. I don't know why this is the magic number, but this was the case for all my orgs, my boss' much larger orgs, peer orgs a few hops a way, etc. The math just keeps working out.

If you take this personally or over react, you will burn out. More so because you have very few levers to influence the situation. It's a truism that most people leave "bad managers" not "bad jobs" but your ability to intercede is greatly limited by distance. You won't know your skip reports' hearts and minds as well as you know your directs. You won't be in the room to understand the exact cocktail of micro and macro-behaviors that caused one of your employees to quit. Sure, you can fix "problem managers" that are driving away people in droves, but that's usually not the issue. Get comfortable with turnover, and build an organization that can handle this disruption while rapidly training new talent.

A corollary to this "law of large numbers" is that someone's grandma is always dying. Substitute death for chronic illness, birth, or family emergency and you get the picture. Some large fraction of your organization will always be on a leave of absence, especially at BigCo where there are many types of centrally supported and protected leave benefits.

You have to preserve enough slack to deal with the constant churn of terminations, resignations, leaves, and onboardings. It probably isn't an epiphany that you cannot run your organization at 100% utilization, but the sheer scale of the required holdback probably is–in any given planning cycle, you should only intend to utilize 70% of your overall organization. Yikes. That doesn't even factor in how many (acute or chronic) underperformers you are carrying. "I have 100 employees, we can do so much!" Bzzzt, wrong, try again. You have like...50?...actually useful humans at any given time.

10. Create a community of practice for managers.

Reading this far you are probably feeling vicarious exhaustion. Management can be like that. On one hand it feels amazing to create an environment that allows people to do the best work of their lives and to experience the self-worth and self-actualization of collective success. On the other hand: so. much. bologna.

- You pour all your energy into your reports–doing your best for them and the business–but who looks out for you?

- You spend most of your time at work, but forming real deep friendships is muddied by hierarchy.

- Managers tend to self-isolate and focus on their team. Often the only time spent with other managers is in a group setting with your boss ("the weekly staff meeting"). The boss' presence dissuades managers from sharing their problems (the boss might be their problem!) and implicitly encourages competition.

You can shed all of these burdens with one simple trick: a community of practice (CoP). A CoP is a group of people who share a concern, passion, or problem, and deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area through ongoing interaction and shared activities. Key to a CoP is shared commitment to a domain, the development of community through mutual engagement and joint activities, and the creation of a shared repertoire of resources, experiences, and tools through practice.

I have found many managers resist forming such a group–they question the possibility and payoff of making a meetup like this work. This is a mistake. Well integrated managers working together have incredible potential to move work forward: sharing and assimilating information, consulting and strategizing on problems, and forming power blocs for ambitious org-wide schemes. All the better that it creates a safe, trusting environment...a "home base" you can always return to when the going gets rough.

I try to foster this by turning my "weekly staff meeting" into something of a "management repair garage" where we consult with each other on the conundrums of the day. This is a good starting point, but a true community of practice requires going further. Ideally, a regular meeting without "the boss" present to avoid competitive pressure and to encourage joint problem solving rather than deferring to power. To learn more about this concept and the problems it solves, read In the Middle by Barry Oshry (side note: try reading a book that talks constantly about "tops" and "bottoms" without laughing).

11. Managers scale by the number of problems, not the number of reports.

I have witnessed extremely skilled and experienced managers fail with only 5 reports. I have also seen managers succeed with as many as 25 directs (I did just that...twice...and it wasn't as bad as you might think). What gives? What is the ideal "span of control" for a single manager?

Managers scale linearly i.e. O(n), but, hot take, I don't think n is "number of reports." Managers scale by the number of problems / goals / areas of concern they own.

Before I get completely dog piled, let's be clear, there are limits. I don't think a single manager can handle an unlimited number of people (just the effort of allocating work, giving feedback, and completing performance reviews for 30+ people is staggering). Even above ~12 people you need some adaptation techniques including fortnightly 1:1s and hiring exclusively staff+ tech leads...but the point is it is possible to do so and thrive.

The real limiter on managerial effectiveness is how many discrete, non-overlapping problem domains they own. Each area requires dedicated care and attention to (1) understand the goals, (2) formulate strategies, (3) implement said strategies, (4) build alliances, (5) operate the rhythms of business. These responsibilities are (usually) unique to the manager and, even when delegated to a strong TL, must only be partially delegated in a trust-but-verify sense.

Let me paint two not-so-hypothetical pictures to explain:

- The Mobile Team: every single feature and business objective involves this team because it's the primary interface with the user. The manager(s) must be in tune with effectively ~all the goals of the organization, their respective dependencies/requirements/timelines, and ensure all of this goes off without a hitch. Given their broad exposure, they are in 10+ status meetings per week and, statistically speaking, something is always on fire. When resource contention occurs, they must somehow prioritize between irreconcilable objectives like "support DLP controls for enterprise customers" and "add new social features to incite product-led growth."

- The Performance Team: they own a very specific objective (make it fast). Even though they must work across basically every system/app/component to achieve this goal, it is all in service of one particular outcome. They will divide and conquer to leverage expertise (workstream 1: "speed up database queries;" workstream 2: "progressively load the web app"). There's still more work to go around than people to do it so prioritization is key, but the trade-offs are all tractable because you're not comparing apples and oranges like the mobile team.

Both these teams might be quite large (10, 20, even 30 engineers) but the mobile team likely needs 2 or 3 dedicated managers while the performance team needs only 1.

A note of caution. While it's possible for a single manager to lead a large group, that large group should not run as a single team. That is to say, "all the people who report to me" no longer makes sense as the definition of a team. Managers with large spans will end up running two or three teams. You've surely heard of "two pizza teams," Dunbar's Number, and the like. These rules-of-thumb still apply when forming high-functioning teams as they speak to the limits of human social psychology, but shouldn't be used to determine how many managers you need....that is a different problem altogether.

12. Delegate and let things fail to sharpen your team.

Pretty much every manager under the sun has heard they need to delegate. Too often, however, what gets implemented is a sort of faux delegation where you're still actively watching all of the proximate actions and even volunteering extra support for the really tough bits along the way. You tell yourself this is what it means to be a good manager–don't throw your report to the wolves and all that–but the end result is the same time demands as if you were personally doing the task. Bonus: now you're also subject to the stress and anxiety of working through someone else. In the end, you learn very little of what this person can handle solo.

Here's the very raw deal we all get at BigCo. Everyone is doing 10 things at once, and success is determining which 2 absolutely cannot fail while letting the rest go. Spending any time at all beyond the occasional 1:1 on those other 8 things is not a good idea: you're either going to deliver a weaker outcome on what really matters and/or sacrifice your personal life to make up for lost time.

This is especially hard once you enter middle management. The stuff you need to delegate isn't straightforward tasks or even entire projects...they are things like:

- "The PM's roadmap is a sham and their management isn't going to do anything about it. Go make sure we have a real product strategy please."

- "A dependency has refused a feature request that blocks our most important objective and their Director refuses to even meet with us–figure it out."

- "We keep having back-to-back production incidents...make it stop but also don't slow down feature velocity using either science or magic."

These XXL, black diamond ambiguous problems are not just hard to solve but critical to the long-term success of your team. They are strategic, require extreme tact, and it's possible to fail for reasons outside one's control. The exact sort of thing you feel in your bones is your job because it's your org and you cannot leave it to chance. Spoiler alert: you should absolutely leave it to chance.

First off, remember what it was like to be a line manager. You were smart/capable/accomplished. and hungry for an opportunity to do work that had real import and stretched you to your limits. You were ready to leave the kids table and it took waaaaay too long for your boss to trust you like that. Don't repeat that mistake.

Part of this is recognizing just how far you've come, you're no longer on the "ground floor" and there are people below you who are absolutely phenomenal leaders and operators. I know ego isn't in vogue right now, but pretend humility doesn't help and having a more realistic self-image lets you grok just how gnarly a challenge your managers can probably handle. The stuff you should be focusing on is the real nightmare fuel (e.g. "we are at risk of churning our largest public sector customer and nothing we do seems to appease them"). There is real opportunity cost to not tackling those issues yourself–far in excess of letting a few lower priority things potentially fail. The classic HBR essay "Who's Got the Monkey" is a great starting point for learning to resist making everything your problem.

Second, delegating critical ambiguous problems helps precisely measure the limits of your leadership bench...how much you can trust them with and not have it come back to bite you in the ass. "What if they fail?" Yes and what if they do fail? They will either learn and grow, or a pattern will form and you'll understand that person needs to be fired. I know that sounds very black-and-white, but if someone on your bench can't be trusted with weighty important problems, it only holds you back because everything will just end up on your plate. Managers don't usually fail for mundane reasons like failure-to-ship or misconduct...there's always some amount of vaguely good progress and other positive-ish stuff happening. As a result, it's easy to accidentally retain a management team that is more decorative than functional.

If you never trust your managers with the real, grown-up problems they are supposed to solve independently, you'll wake up one day (after an all-nighter most likely) wondering why everything requires your personal attention and "wouldn't it be nice if I could hire another me to help load balance?" You will have none to blame but yourself.

A team honed with real honest-to-god delegation is ridiculously sharp. With a deep bench, it will feel like you have nearly limitless capacity and your work-life balance will be...at least manageable 🙃. Big hairy problems become mundane and tractable. You'll start to wonder "does the team even really need me any more?" As times change, people leave, orgs shift, there will be super stars primed and ready to enter the senior leadership team. All is right with the world.

Delegate things you think you shouldn't; manage out the failures; focus on the one maybe two things that only you can solve. That is the recipe for a thriving Director/VP.

13. What the hell is "half" an FTE?

If you show me your quarterly OKRs and have "0.5 FTE" in the staffing column, I throw the entire plan in the bin.

"Half a person" is not a real thing, I'm sorry. When they come into work, what does this person understand their job responsibilities to be, exactly? "On Monday and Tuesday, I work on improving the mobile document scanner. On Wednesday and Thursday, I work on rebuilding the onboarding flow. On Friday, we make waffles!" Kill me.

Such plans usually fall victim to a number of common errors:

- Impossible Precision: planning over such large timescales (months/quarters/years) down to the level of fractions of a person is just not possible with the low quality, fuzzy data we feed into the planning process. Fixing those inputs to increase precision is usually impractical and not strictly necessary. Understand that for most senior leaders, they will abstract this all away as "John Doe = Project Foobar" or even higher up "Team X = Project Foobar."

- Binpacking Assignments: thin slicing individuals this way encourages stuffing the team full of commitments. Even if you leave some slack built in and don't fully allocate, your team still ends up on the hook for many different goals simultaneously...each of which may fail or need extra unplanned help. It's a recipe for overpromising and underdelivering.

- So Many Silos: you end up with multiple projects that have only 1 person assigned. These projects will grind to a halt the minute said person takes a sick day or gets pulled into a production incident. If they leave, you have no backup plan. And they probably will leave because they'll start complaining about feeling alone and isolated day in, day out.

Just don't do it. Restrain yourself from faulty "manager math" and plan in whole FTEs only. In practice, you may be able to pack in more work than anticipated but that is far better than finding yourself up against a wall halfway through the quarter.

14. Managers are inherently insecure.

(that includes me, to be clear ¯\_(ツ)_/¯)

Adding more managers to your org carries a bunch of additional hazards. Each manager is a new mouth to feed: a bright-eyed, career-oriented, driven individual who gets bored easily. They expect important work, a fresh bushel of headcount every year, and meaningful opportunities to grow into senior leadership (despite there being, you know, only one next-level-up job and you're currently busy doing it).

As org priorities change and headcount shifts (well, shrinks, it's 2025 after all), it will be a three-alarm fire to ensure each manager feels special they have good scope. Any overlap at all between adjacent managers and you can expect confusion and anxious questions in 1:1s about "what do I really own? Where does my responsibility end and so-and-so's begin?" No answer you offer will satisfy, trust me I've tried all of them including "just...work...together!?"

This also pops up for innocuous reasons day-to-day. If a peer suddenly pokes their nose into someone's area, hackles are raised...even when there's no nefarious intent (in fact, maybe you asked because something is too-important-to-fail and wanted to swarm extra people onto the project). You will spend way too much effort playing therapist and ensuring each manager knows they are the prettiest girl at the ball.

When packing your ranks with the maximum number of managers it can support, you give yourself more problems not fewer. There will come a day when there aren't enough discrete swimlanes for everyone and there isn't enough Advil on Earth to deal with the headache that will ensue.

I had enough slack in my latest org to add one extra manager. While it would have helped load balance some, it also would have been a long-term headache and limited career advancement for several of my directs. Now that I've left management, I'm extra glad I didn't because ensuring everyone was well taken care of in the aftermath reorg was hard enough as-is.

Add managers to your org with caution. The pool can only fit so many swimlanes and no amount of doe-eyed optimism about "working together" can fix the inherent territorial insecurity endemic to the management caste.

15. Dig until you find what people really believe.

As you ascend the ranks people are less and less honest with you. This can happen when there is fear of reprisal or folks feel they are being judged for character and competence in your presence. There is a pretty obvious incentive for looking smart in front of the boss. This also happens indirectly because, the higher up you go, the more steeped in corporate culture your immediate directs become. You'll never get a straight opinion out of anyone ever again because everything they say has been eviscerated by a corpspeak translation filter.

No one is going to walk into a one-on-one with you and say "this project is $*%&ed, we made the totally wrong architecture decision, and my manager is forcing us to ship it anyways. Oh by the way, the dog died yesterday." You'll get some polite drivel like, "the project is taking longer than expected because we made a challenging trade-off that had some unanticipated consequences. We're working hard to get everything back on track."

You cannot make good decisions if the only information you're fed are these super anodyne, rose-colored, indirect nothings. Fixing this is hard; people are afraid of revealing their true beliefs. Unvarnished truths open them to judgment ("wow you really believe that?") and it's hard to treat everyone and everything fairly and with the right amount of nuance. I get it: you might exaggerate or misstate something or give me a half-formed thought that you'll later be embarrassed by...just. spit. it. out.

I really value people's intuitions. When one spends all day/week soaking in a given area and problem, your off-the-cuff thoughts are likely more accurate and revealing than any amount of armchair analysis the skip-level does from a distance. To get at these nuggets I often need to push hard...even to the point of discomfort: "what do you mean by that? what, concretely, has happened? what specifically would you do in this situation? no, you have to pick one thing, what is it? I don't understand what you just said at all, try again."

In doing so I have to perform radical acceptance....to make others feel safe offering raw truths and neither judged nor dismissed. This also means not reacting immediately to the information provided (I can't just rattle off "ok here's what we're going to do"...that might need to come 1 or 2 meetings later). Some people buckle under this sort of pressure/attention; so be it. Most would agree its better to be a part of a team that gets shit done rather than getting hung up on polite performative doublespeak.

There's this really amazing quote from Barry Diller (media mogul of ABC/Paramount/Fox fame) on the Prof G Pod that perfectly encapsulates this idea for me:

I like creative conflict, I like argument, I like the whole concept of arguing things out of passion because all I care about is instinct. In order to hear the truth of something you have to push through and get to "what does that person really believe." [...] I just think it's the most productive way to manage.

Get really good at cutting straight through to the heart of things. From here on out, everyone is going to be talking around their real issues.

Leading from the Front

16. Power exists to be used.

I don't believe in Servant Leadership. There. I said it. I view pure Servant Leadership as an abdication of many of the core responsibilities of a manager that is ultimately a disservice to my team.

- What someone wants and what's best for the company (or even their own career) can sometimes be in direct conflict.

- Some situations need immediate action (think: emergencies) and there isn't time for democracy.

- More generally, there are diminishing returns to unending deliberation. Teams can get stuck in planning paralysis when there is no clear right answer.

- The manager's standing in the organization directly impacts the work and opportunities for everyone reporting to them. While it's true your success comes from the team actually doing the work, so too does the team's chance to receive such projects come from your personal victories. It's symbiotic.

- No team is an island and you must actively align your group with the will and needs of the broader organization. Sometimes that means shutting down side quests, science experiments, and other larks when enough is enough.

- The org must believe you're able to channel it's resources wisely and to great effect, or your team will be starved to death with shrinking headcount and fewer/less important opportunities.

- Depending on the task-specific competence of a team member, you may need to do a lot of telling (or at least selling) to get the right level of performance.

I'm not evil, I don't believe in command-and-control either. Management is definitely a type of service job, but you have multiple constituents (your customers, the company, the organization, your team, etc). Trust, autonomy, openness, and a focus on collective success (over individual success) are all traits of healthy teams and the best managers create that. Sure these are all components of "Servant Leadership," but most managers get hung up on the touchy-feely and forget to, you know, actually lead! The formal theory usually needs so many qualifiers and addendums to be at all practical that it isn't worth the attention it receives.

There is a reason we have hierarchies at all and don't just run huge flat orgs. Effective use of a power can be a tremendous force for good in the workplace:

- Leaders are exposed to massive amounts of information. While we should strive to share and be transparent, a coder who once-in-awhile thinks about business strategy cannot hold a candle to someone who has 100+ people across functions feeding them info all day, every day. Leaders can quickly divine the ideal path through ambiguous, high-stakes situations.

- When irreconcilable differences create deadlock, leaders can resolve the conflict and set the team on a forward trajectory. Healthy escalations are not about "tattling to Mom and Dad" but recognizing that sometimes teams can hold mutually exclusive goals that need untangling.

- On that note, if someone really is behaving badly and causing problems, leaders can quickly end it, one way or another.

- There are many decisions that simply don't matter or where there is only one situationally and politically viable path forward. Leaders can quickly remove unnecessary degrees of freedom and improve velocity with thoughtful proclamations.

- If you want to quickly influence the way hundreds of people work, give someone a very high title and make them extremely visible. This is often more effective than 1:1 performance coaching because employees see "if I do these things, there is extrinsic reward waiting for me."

As always, with great power comes great responsibility. I strive to find the intersection between what individuals want and what the company needs– maximizing their opportunities for self-actualization while continuing to fulfill my obligation to the institution. Swinging the gavel of authority feels really good (it's even somewhat addicting) but try to restrain yourself to moments where the alternative is significantly more painful for everyone involved.

17. The "E" in "EM" stands for Engineering...or did you forget?

Engineering Managers (EM's) must be technical...and I don't just mean "vaguely understand what's going on and professionally wrote code 10 years ago." The most successful EM's I have seen:

- Are excellent software architects, understand the entire system, and know how to reason about complex design decisions.

- Have a finely tuned barometer for what's hard and what's easy, and can represent the team in early scoping and feasibility discussions. Their finger-to-the-wind estimates can be trusted.

- Can triage bugs and customer issues quickly with a reasonable degree of accuracy, ensuring the right person or team is activated.

- Get "how things are built" in their company and what aspects of the tools and processes are smooth vs. toilsome. They can articulate where the tech/org/process debt is and which debt is worth paying off.

- Know enough about the code, frameworks, and patterns used to adjudicate technical debates, identify and shutdown the really pointless discussions, and unstick their teams.

You cannot do any of this if your technical skills are weak/out of date, or you never touched a line of code in your present organization. For me personally, at an absolute minimum this requires:

- Reviewing designs and participating in ~most design discussions.

- Doing code reviews on a regular basis (but not all of them, to be clear).

- Participating in incident response / chasing down production alerts...even holding the pager at times!

- Make hands-on contributions off the critical path. I usually try to pay down toil and tech debt (fixing flakey tests, automating tasks, quiescing noisy alerts, root causing low priority issues that might otherwise get closed/backlogged forever).

- Researching and keeping abreast on the latest practices and frameworks both within and without your company. Give tech talks and educational brown bags (the best way to learn is to teach, after all).

These contributions build up the technical intuition required to guide the team and represent your area in cross-functional discussions....but, spoiler alert, this is hard. Finding time to do all of the above, while not neglecting your people manager responsibilities, and also not lapsing into outright micromanagement, is something most people screw up. This is why you often hear low-brow advice like "manager's shouldn't code!" But that isn't a good strategy, it's a clunky/imprecise guardrail to help new managers avoid going back to their comfort zone (code) and ensure senior managers don't turn into micromanaging despots.

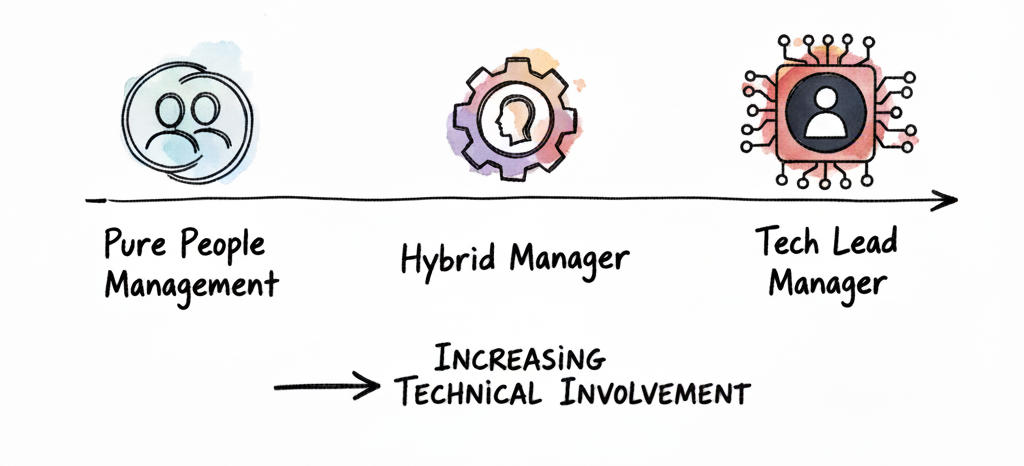

That said, there is certainly a spectrum here:

Pure people managers have a number of predictable failure patterns: they become little more than information routers/delegators (what value are you adding exactly?) or the team will end up making a series of terrible technical decisions that they fail to detect or prevent. On the other hand, hardcore "Tech Lead Managers " (TLM's) are really doing two jobs at once, and probably doing a bad job at one aspect or another. They often burn out and leave their teams in a lurch, or fail to develop a bench of competent TL's.

Here's the kicker, I don't think the right answer is "be the perfect goldilocks mix of TL and manager all the time." You should:

- Provide the leadership your team needs: I have (had?) a "pure people manager" for one of my team's...and, despite what's written here, I think they are perfection. They were exactly what that team needed: someone who could set up the environment and remove chaos, align the complex web of teams/partners, and provide the loving/caring attention and coaching needed to unlock everyone's potential. There was no lack of technical chops in that group, but without proper structure they would fail. Likewise, there were teams where all their problems tracked back to an absence of technical vision and execution ability, they needed a visionary TL with autocratic powers to get out of the never-ending break/fix/break/fix loop. Figure out what your team's biggest problems and gaps are, and then implement the appropriate leadership strategy.

- Play to your strengths: too much effort is wasted trying to address one's weaknesses (where all you can often do is grow from being "really terrible" to "kind of okay, I guess"). Understanding your unique, standout strengths as a leader and exploiting them to maximum effect is how you can have a really outsized impact and get ahead in your career. This is the whole philosophy behind Clifton StrengthsFinder. For myself, I recognize that being a "TLM" is doing two jobs at once but I wouldn't have it any other way. I first orient myself by tending to the details, and then progressively zoom out to higher levels of abstraction until I understand the whole organization. I approach the job as incrementally evolving the whole socio-technical system into better, more optimal states. Technical details are the basis that enable me to identify avenues for improvement and impact that elude my peers.

Understand the type of leadership you excel at providing, and find opportunities/problems that are most likely to yield to that sort of leadership.

18. Just take the vacation, it's always "bad" timing.

I am hoarding PTO like a dragon hoards gold. Seriously, if I quit now and got my vacation days paid out I would make more money than all of my stock picks in the last year (side note: do not take trading advice from me).

It just never seemed like the "right" time to take a week or two off work. Something would surely burn to a crisp. The emails would keep on coming. I would get back and just be "two weeks behind" which was strictly worse. This led to bargaining with myself: I'll take that vacation after performance reviews are done / after promotion season / after annual planning. In 8 years I have taken...3 weeks of vacation? I think? Opps.

This one is simple: it's always "bad" timing but never as bad as you think. It's far worse for everyone if you're burned out and not playing at your best. Just take the damn vacation. Even better, make sure it's at least two weeks long so people don't just wait for you to get back. This helps pressure test if you're really building a team that can thrive on their own, and focus your bench building efforts when you return.

19. Maybe only 1 or 2 decisions per year really matter.

There were times when it felt like all I did all day long was "make decisions." Be it what things to prioritize, who to assign to those projects, short-term technical decisions, long-term architectural roadmap items, with whom to form alliances, or where to host a team dinner. Any time the team was picking between two ambiguous and equally good sounding options, I was the vending machine they punched a few quarters into and got a decision.

This usually evokes one of two feelings on any given day:

- Fatigue: it would be great if someone could send even a single chat message that didn't require you to choose between two horrible options with long-term existential consequences. Every ping will trigger a fight or flight response: "oh boy, here we go again." None of these decisions ever come quickly–it'll always lead to some amount of homework to figure things out–and worse, there's no way to make everyone happy. You'll descend down the mountain, stone tablets in tow, to a room that is 50% elated and 50% grumpy with any given proclamation.

- Euphoria: nothing can stop you! You're a machine for organizational efficiency and engineering efficacy. You seem to reap but never sow. Knowledge is power and power is one hell of a drug. This is the runner's high of being a manager and you couldn't imagine going back to a world where you didn't get to make all these decisions constantly.

Whether it's negative or positive, if you're like me, you may start to believe "my organization wouldn't survive without me." Well, bad news, I'm here on the other side of nigh on thousands of decisions big and small with the gift of hindsight: almost none of them mattered. They were the managerial and engineering equivalent of choosing where to grab lunch: "McDonald's or Taco Bell" (the correct answer is Taco Bell, btw). While it was important to make some decision, any decision and not get stuck in planning paralysis, the actual outcomes were not significantly different or better.

On the flip side, I can distinctly pin point one or two decisions each year that had massive, long-term, existential ramifications...usually because I made those decisions incorrectly. From the time I gave in to lesser demons and appeased my boss–supporting the creation of an over-engineered framework that has created O(10) SWE-years of technical debt and slows everyone down–to the time I rejected a rewrite project claiming "we will release and weigh the ROI of a rewrite using production data"–wasting a year struggling to fix all the bugs and never actually releasing anything.

Horror of all horrors, these decisions at the time didn't stand out as particularly remarkable or momentous. They felt the same as the usual parade of mundane bullshit that traipses through my inbox–there was no tell that we had a "big one" on our hands. Even then, I thought my decision making rationale at the time was sound/logical, and yet these are some the biggest mistakes I've ever made. When made correctly, a singular decision of this nature can pay for yourself and your entire team in one fell swoop. Maybe it's avoiding a pointless project, some very shrewd hardening that prevented an epic production disaster, or making a key hire that permanently alters the trajectory of your team.

There is no silver lining in this story. I haven't discovered a bullet-proof method for clocking which decisions truly matter. Bezos' one-way door vs. two-way door thing is a cute analogy, but not at all definitive. First off, all the examples I can think of absolutely presented as two-way doors, but confirmation bias is a bitch and you're likely to ignore the evidence you chose the wrong door. Second, every decision is a two-way door when you command 50+ SWEs and have hundreds-of-millions of dollars in operational budget. What couldn't you "undo" if you really wanted to!?

My only advice is to postmortem every mess up to find the common traits and patterns of weighty decisions, and to build a library of heuristics you can apply going forward. For me, a few signs I might be dealing with a Big Decision are:

- ~8+ people are involved or directly impacted by this decision. It determines what they work on and how they do it.

- Multiple parties have displayed emotional attachment to the decision.

- Back-channeling has broken out. No one is willing to say "I disagree" publicly.

- I feel any urge to optimize for appearances (i.e. this decision seems important to how me or my team are perceived by people who matter).

20. The dopamine reward loop for managers totally blows.

No one wants to hear their leaders complain about how hard leading is ("my crown is too heavy"). But if you couldn't tell from this post...IT IS. Researchers at Columbia University surveyed nearly 22,000 full-time workers and found that middle managers are more depressed and anxious than any other group. Longitudinal studies found ICs that became managers and later middle managers were more likely to become depressed and anxious. Cool cool. No big deal.

There are probably lots of reasons why that is, but I think it has much to do with our complete lack of a dopamine reward system. This is the built-in motivation circuit in your brain that releases the chemical dopamine when you do something pleasurable or achieve a goal, making you want to repeat that behavior. It evolved to reinforce survival activities like eating and socializing, but it also responds to things like accomplishments, unexpected rewards, and even anticipating something good is about to happen.

When you were a hands-on IC or even a line manager, every day you could do something that delivered a fresh hit of dopamine: checking in some code, squashing a bug, helping a peer or a customer.

As a manager, your dopamine reward loop is long (like, really looooong).

- You own entire major business objectives that might take 2/3/4 years to land.

- Coaching and training someone on your team might not show tangible progress for months...and sometimes it doesn't stick making it all feel like a waste!

- Process changes can be implemented quickly, but you won't know for sure if it generated the desired outcome (e.g. "faster launches") for multiple quarters.

- Closing a new hire is great and all, but the real test is to see how well they onboard and if they can deliver valuable work. See you in 6-9 months!

Each day is spent nudging a complex socio-technical system into a more optimal (we hope) state. The individual activities that go into that do not return the same feeling of accomplishment:

- Coached Donald on conflict de-escalation techniques to use on Megan. They still hate each other.

- Reviewed Mike's design doc and connected him with experts on the SRE team. This design isn't going to work and the SRE's are a hail mary.

- Argued with Scott about the frequency of status updates. No conclusion was reached.

- Presented our reliability strategy to exec leadership and got zero feedback.

- Traffic spiked and we ran out of resources, asked the team for postmortem. They were not happy with me and just wanted to ignore the issue.

- Politely refused a request from a peer team that was pathologically insane. They will escalate to my boss tomorrow.

In practice this translates to many dark weeks without the joyous spark of accomplishment. These long loops can easily get disrupted entirely (project delays/cancellations, someone quits, etc). I think this is why every manager I know is obsessed with fitness–it's something entirely within our own control that can become a sort of daily dopamine supplement!

Some managers try to recreate the dopamine reward loop they had as an IC with fun games like inbox zero and manicured todo lists, but this is just delaying the inevitable or outright wasting your time. You have to ween yourself off this stuff–things will never be the same from here on out.

21. Truck routing is NP-hard and yet Fedex still manages to deliver your packages.

If you're like 1 in 5 Americans, you probably had a package successfully delivered to your home today. This happened in spite of the fact that optimally routing trucks is a form of the traveling salesman problem, for which there is no polynomial time solution. We haven't had computers (or humanity, or Earth) long enough to solve TSP so what gives? How is this possible?

Someone made a decision: a good-enough heuristic that happened to work well for the street grid in a given city. It might not be optimal, but you got your mail in reasonable amount of time didn't you?

You too will be forced to make such decisions under ambiguity. Decisions where:

- You have incomplete information.

- There is no established norm or best-practice solution.

- All available alternatives feature significant trade-offs.

- There is insufficient time to identify the best possible option.

- You may need to act first to get a sense of how cause/effect work (a complex or chaotic domain in the Cynefin sense).

There is simply not enough time to be empirical and deductive about absolutely everything. The usual engineering org is under so much pressure (either from within or without) that it is impractical to analyze everything until you're absolutely certain what the right answer is.

Ultimately, a leader creates the clarity for the appropriate decisions and actions to emerge. In the event of outright paralysis, a leader personally takes action or makes the decision. This will put all of your intuition and experience to the test. I have always been a fan of Amazon's leadership principle that states, "Leaders are right a lot. They have strong judgment and good instincts. They seek diverse perspectives and work to disconfirm their beliefs." I have my own much more sarcastic version of this principle: "it's not just good, it's good enough."

I am not advocating for making random, under-considered choices, but rather getting very fluent in techniques for reducing ambiguity, and thereafter comfortable not knowing whether you're right or wrong and having to trust yourself (or your team).

One of the most eye-opening books in my journey to master ambiguity is How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of Intangibles in Business by Douglas W. Hubbard. In the book, a definition of measurement is proposed:

Measurement is a quantitatively expressed reduction of uncertainty based on one or more observations.

This puts Big Tech's data and metric obsession in a totally different light. Rather than thinking about "measuring something" as a way to observe a physical quantity in the world (think: the weight of some potatoes at the supermarket...there is only one right answer), it should be thought of as a way to reduce uncertainty around a decision you're trying to make...at least until its no longer economically beneficial to do so.

Decisions like "should we build feature A or feature B?" and "how much effort is this project?" and "what in the world do my millions of users want from me?" can all have uncertainty reduced tremendously by some basic proxy measures and heuristic estimates. If you passed the algorithm and riddle festival that is the traditional Big Tech Interview, then you are at least serviceable at forming Fermi Estimates. Even just estimating ranges for unknowable quantities can be useful in navigating these ambiguous situations e.g. "this project will definitely take more than a month, but less than a whole year" or "we can surely capture 1% of the total addressable market with this feature, but there's no chance we pass 5% any time soon." Simple experiments, iterative launches, and existing metrics can be used to nibble away at unknowns and enable enough collective sense-making to unblock a decision.

It's through this lens that I went from rolling my eyes at the weekly business review (and the many games my fellow managers played to make it look good) and learned to love metrics.

22. Hold a high bar, respect the opportunity

OK, I know corporate values seem super hollow to most people these days, but I really do think Google was on to something with "the three respects." Specifically, "respect the opportunity." As much as working at big tech can sometimes feel like one non-stop farcical Silicon Valley skit, it is truly an honor to work on products used by most of the human population and to create a positive impact at that scale.

Moreover, at an individual level, getting a job in big tech is fundamentally life changing. From the long-term career prospects, to finding a community of like-minded people (aka...nerds), to the staggering amount of personal wealth it generates and everything that unlocks. The American Corporation is an amazing engine for social mobility and in an age where big tech is the top of the corporate heap, nothing comes close to a FAANG job for its ability to lift individuals out of poverty and set them on a path to lifetime security and abundance.

I was literally homeless for part of my childhood, now I have more money than I know what to do with and short of, like, outright nuclear war, I will never experience precarity again.

For so many, jobs in big tech are a lifelong aspiration that they work for years and years to accomplish. Studying all night long to get CS degrees, foregoing relationships and friends for years at time, moving across the country, and grinding out LeetCode like their life depends on it.

This is why I have a reputation for being a bit of a hard-ass as a manager. I absolutely do not tolerate mediocrity or anyone coasting, and you shouldn't either. Even the lowliest entry-level L3 SWE job is a role that someone, somewhere is dreaming of with every fibre of their being. With this comes the need to show people the door when they're no longer holding up their end of the bargain. I have watched many managers waffle when someone is failing despite repeated coaching and feedback. It's bad for the team, it's bad for you, and it's bad for them to let problems like this go unaddressed. Firing people is one of the most emotionally ruinous things a manager must endure, but it must be done. As a manager you have a duty to the company, and in my mind, society, to ensure these opportunities go to those who truly deserve them. Be uncompromising in the standards you uphold.

Career Growth

23. Figure out what your boss is trying to do and help them do it.

Maybe this seems pretty obvious, but I have seen far too many people screw this up.

Your manager has a mission: something they are trying to accomplish or deliver. Maybe it's something handed to them by their boss or it's a strategy/idea of their own making, it doesn't really matter. The point is, just like your own staff, you are a cog in the machine that is grinding towards that mission. Understanding the role you and your team(s) play in that machine is critical to ensure you build an organization that is fit to purpose.

Where I see rookie managers go wrong is when they grow to a point where they believe their job is to create and implement business strategy. Usually this is after 2 or 3 years nailing the TLM and/or execution-oriented management gig. They get antsy, "what's next!?" Someone gave them a copy of Rumelt's Good Strategy Bad Strategy and now all the world's a nail for the hammer that is Diagnosis/Guiding Policy/Coherent Actions. They never actually take stock of what role they and their team plays in the broader organization, and so start doing the "next-level up" job (or maybe more like next-next-next level up job, it's BigCo after all). What happens next is a tale as old as time:

- Rookie manager proposes a grand ambitious strategy for their team (or maybe even several adjacent teams).

- Their leadership team shows little interest and continues to assign work like normal to rookie manager.

- Rookie manager tries to bend all assigned work to their strategy, constantly selling the team on their "amazing" vision.

- The strategy never fully materializes because it's not actually driving action in the organization.

- The team becomes numb to all this "strategy" stuff because it just seems like a management bed time story and not reality.

- The rookie manager continuously advocates for their strategy in every meeting they can wedge it into.

- Their leadership team grows frustrated having to constantly placate and steer this person back onto the train tracks and starts giving them the cold shoulder.

- The rookie manager grows disillusioned and quietly gives up, bemoans reporting to a leadership team that "doesn't have a strategy and just doesn't get it."

Look, I'll be honest, I've walked this path. I've managed people who have walked this path. It always ends in tears (and quitting). This is what we mean when we say someone is "out of alignment with the org." As usual, Camille Fournier can explain it better than I can.

I have continuously returned to this quote from Chad Fowler (of Wunderlist fame, RIP to the best todo app ever):